Nobody Swims Downstream: Timeless Lessons For Personal Growth

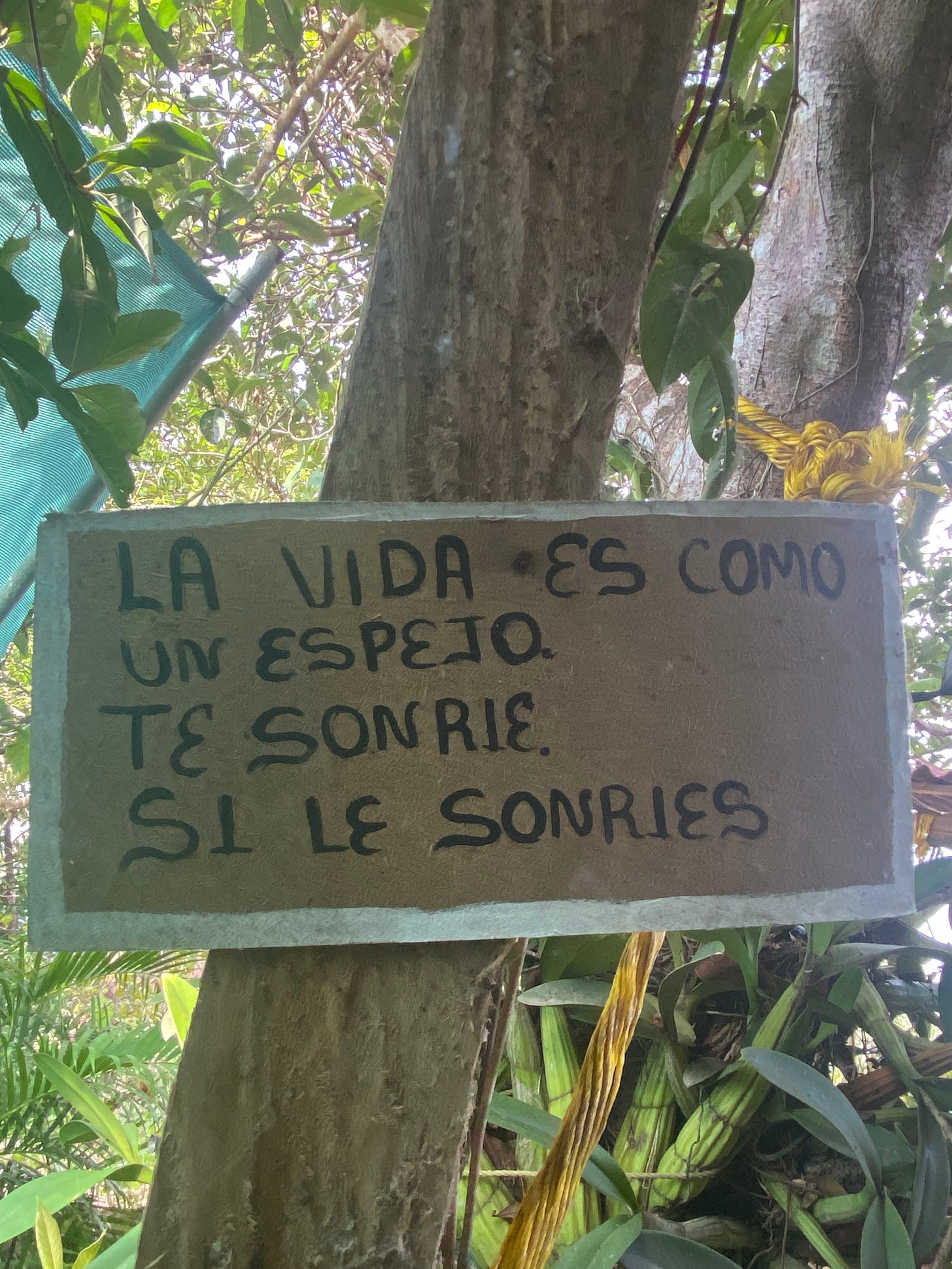

Life is like a mirror. It smiles at you if you smile at it.

I just returned from helping to support a retreat for First Responders in Mexico. After the retreat ended, a few of us went to lunch one day to a rather rustic place in the jungle. It was full of signs like the above. The place we stayed was a few minutes from the restaurant and, again, very rustic with tree branches for handrails, no A/C, and only cold water. However, this place also had their versions of signs (or paintings):

While I joked that this was my favorite piece of Mexican décor, another way to look at it is, well, (quite) an empty canvas. It is whatever you make it. It reminded me of a lesson I shared in Navigating Chaos: How To Find Certainty In Uncertain Situations, which was:

How you see the problem is the problem.

Here’s a different lesson from the same story…

The Story: Swimming in the Pacific

BUD/S (SEAL training) is six months long and divided into three phases. Every week in BUD/S you have a 4-mile timed run, a 2-mile ocean swim, and an O-course (obstacle course) run. If a student fails an evolution, he is normally given an opportunity to try again. Rarely are they given a third attempt, but it does happen.

Anyway, one student in my class, who I’ll just call Baker, failed the swim one day in third phase. He blamed it on the weather—the high winds, the whitecaps, the strong current. In his defense, it WAS a busy day out there. But then again, everybody else passed.

Unfortunately, the BUD/S instructors didn’t care about his excuses. “You can find ‘sympathy’ in the dictionary between ‘shit’ and ‘syphilis,’ but not here” they used to say.

Anyway, the instructors lived up to their mantra. Instead of re-scheduling Baker’s swim for another day that week, they instead told Baker to “get out there and do it again.”

Mind you, the sea state hadn’t changed. It was still choppy, still a strong current, still tough to swim in. AND…Baker was tired. He was angry that he was the only one who had to repeat the swim (although his swim buddy was probably angrier). However, if Baker didn’t get out there and swim the same two miles that he just swam, he would be dropped from the course.

The Lesson: Nobody Swims Downstream

Baker’s situation represents the type of suffering that the Buddha sought to end. The first Noble truth of Buddhism characterizes life as suffering, and the second Noble truth identifies the sources of that suffering as desire and ignorance—desire entailing the clinging to pleasantries and the avoidance of unpleasantries, and ignorance referring to a fundamental misunderstanding about oneself and the nature of reality. Such ignorance isn’t due to intellectual failings but rather to inexperience. What the Buddha found was that it’s our relationship or perspective to whatever it is we’re trying to hold onto or avoid that causes such suffering, or discomfort. How this applies to Baker is if he could transform the thought of having to swim another two miles to an opportunity to strengthen his resolve and getting to swim more than everyone else, then he could change his relationship to the sources of his suffering.

Like most people, Baker was conditioned to resist that which made him uncomfortable rather than just flow with it. He tried to resist the experience of life—which, in this case, was having to swim another two miles—rather than accepting it as is; accepting his reality. Baker’s resistance manifested as acting like a spoiled brat, which only exacerbated his already-poor reputation. The more he resisted, the more suffering he experienced.

But that’s the thing. Nobody swims downstream. Swimming downstream in life is akin to living free of suffering, and nobody lives that way. Nor should they. Although I’ve experienced a lot of unpleasant crap in my life, I’m grateful for all of it because without those experiences I wouldn’t be who I am today.

Suffering ebbs and flows like the tides of the ocean. Sometimes you get caught in a riptide of anxiety, anger, frustration, or impatience, and other times you’re just floating in a sea of joy. So, what do we do?

The only way out is in.

You get out of suffering by looking in—inward at the roots of suffering within yourself.

And then you find acceptance. Don't fight what you can’t win. Stop fighting yourself. Stop worrying about things you can’t control. The more you resist, the more suffering you cause yourself. You can’t fight resistance with resistance.

Now you might be saying, “Well, all this hippie crap is fine and dandy, but what am I supposed to do, just accept everything and not resist anything?” Of course not. When you see an injustice, you fight it. When you see a threat to others, neutralize the threat. These are acts of compassion because they’re rooted in morality. The resistance that I’m referring to is in the mind. In Buddhism, the source of such suffering stems from one or more of the five aggregates. I’ll list them below just so you know what I’m referring to but save their detailed explanations for a future article:

Form. The physical body (birth, death, sickness, old age), material things, the six—not five—senses of touch, taste, feel, smell, hear, thinking

Feelings (sensations)

Perceptions. of our environment and of ourselves. These are things we label and identify as our experience.

Mental formations or volitions. Acts based on striving, complex emotions, thoughts, inclinations, habits, decisions

Consciousness. Awareness of the other four aggregates.

Why are these sources of suffering? Because they are all constantly changing. And because of that—because their change is dependent on conditions—they’re not a basis for true security or happiness, despite the fact that we cling to them for it.

Put it this way, if Baker had entered the ocean from a different spot, would it have been a different sea? Of course not. No matter how hard Baker resisted or struggled to swim, he was still in the water. The ocean doesn't change in any significant way, but it does move you around naturally from one place to another when you don't fight it.

You might be saying, “Well, Baker had to fight because he had to swim against the current.” Yes, exactly. Everybody does, because nobody swims downstream. For Baker, it wasn’t the fact that he had to swim, it was the fact that he had to enter the water again and his resistance to it. It was his unwillingness to accept the ocean of life as suffering.

The ocean of life doesn’t change its nature—it was and always will be an ocean of suffering. But it changed Baker’s nature as he became part of it and as he accepted the fact that he got to swim four miles while everybody else just did two. As he went with the ocean, it changed him. This is the act of surrender.

When you get angry at work at your colleague’s incompetence, or your spouse’s opinion, or your boss’s decision, or your child’s behavior, ask yourself if you’re swimming with the ocean or against it. Are you trying to change them—things or people out of your control—or are you accepting them as they are? Remember, accepting is not the same as condoning. Unfortunately, acceptance is harder because it involves surrendering the ego, whereas condoning is governed by ethics and morality. I may not condone certain people’s behavior because it contradicts my values or sense of justice, but I accept it because those are the mental and emotional tools they were given and are capable of right now.

Conclusion

Baker finished his second two-mile ocean swim, right before getting—not having—to run another timed evolution: the O-course. Not only did Baker pass the swim, but he ran his fastest O-course time to date. The problem for Baker wasn’t “out there,” it wasn’t external. His initial problem wasn’t the fact that he had to swim more than anybody else, or that he was exhausted, or that the sea state was too rough. No. His initial problem was internal, it was how he saw the problem. Ironically, the solution was internal, too, because once he accepted his fate, once he surrendered to the process, he elevated to a better version of himself. He changed his perspective from “I have to do” to “I get to do.”

If you want answers, look in the mirror. Go inward. Remember, life is like a mirror: It smiles at you if you smile at it. And accept the fact that nobody swims downstream.